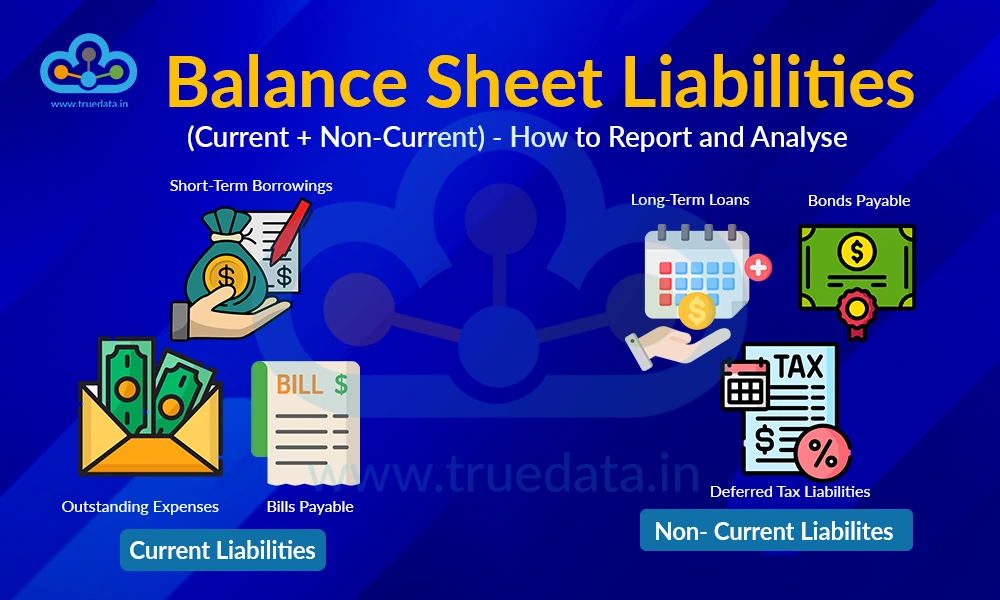

The financial statements of a company are the mirror that reflects its financial position. Hence, understanding these statements is crucial for a complete and accurate analysis. We have covered the balance sheet assets and liabilities in our earlier blogs. Now let us focus on the other component of the balance sheet liability side, i.e., the shareholders’ funds. Check out this blog to learn about the final major element of the balance sheet and how to analyse it.

Shareholders’ Equity, also known as owners’ equity or net worth, represents the value that belongs to the owners of a company after all its debts have been paid. In simple terms, it is the portion of the company’s assets that shareholders truly own. If the company were to sell everything it owns and pay off all its loans and liabilities, the amount left would be the shareholders’ equity. This figure is shown on the company’s balance sheet under the ‘Shareholders’ Funds’ section. A strong, positive shareholders’ equity indicates financial stability, while a negative figure signals that the company owes more than it owns, which can be risky for investors.

The shareholders’ equity is made up of many components that represent the shareholders’ funds. These components are explained below.

Share capital is the money raised by the company from its owners in exchange for shares.

Equity Share Capital gives shareholders ownership rights and voting power.

Preference Share Capital provides fixed dividends before equity shareholders receive theirs, but usually comes with limited or no voting rights.

Companies disclose their authorised capital (maximum amount they can raise), issued capital (amount offered to investors), and paid-up capital (actual amount received). Paid-up capital is the real contribution from shareholders that forms the base of equity.

Reserves and surplus represent the profits and extra funds that the company has kept aside instead of distributing entirely as dividends.

General Reserve, which is created to meet future needs or expansion plans.

Capital Reserve, which comes from profits made through special transactions like selling fixed assets and is not usually given out as dividends.

Securities Premium Reserve, which is the extra amount received when shares are issued at a price higher than their face value.

Surplus (Retained Earnings) is the portion of profit left after paying dividends and is reinvested in the business.

A growing reserves and surplus section is a sign of financial strength and the company’s ability to fund future growth.

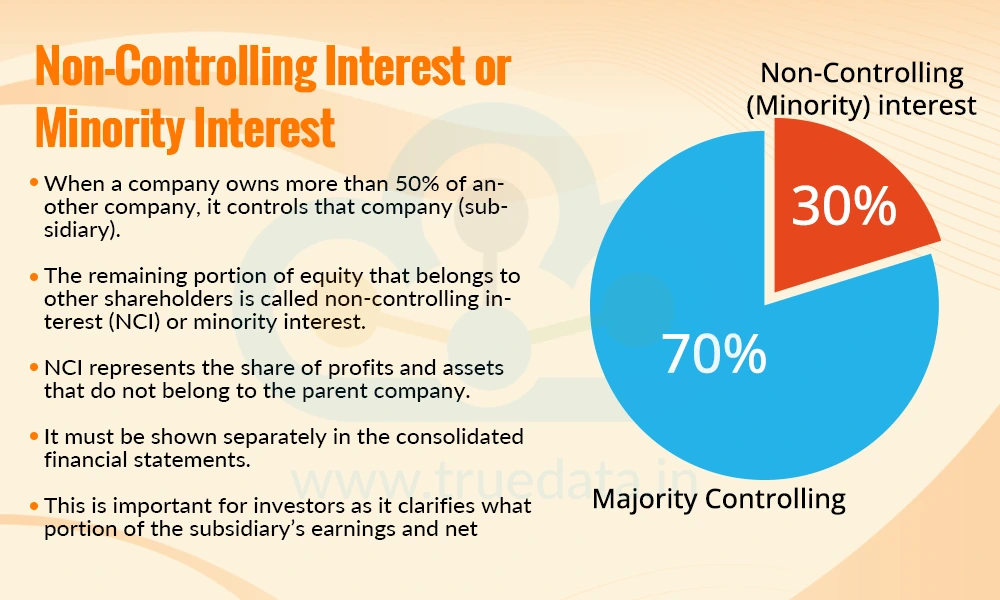

When a company owns more than 50% of another company, it must also show the portion of equity that belongs to the other shareholders of that subsidiary. This is called the non-controlling interest or minority interest. It is important for investors because it shows the share of profits and assets that do not fully belong to the parent company.

Shareholders’ equity can be calculated in two main ways, i.e., using the balance sheet approach or using the capital and reserves approach. Both methods arrive at the same result, but they use different starting points.

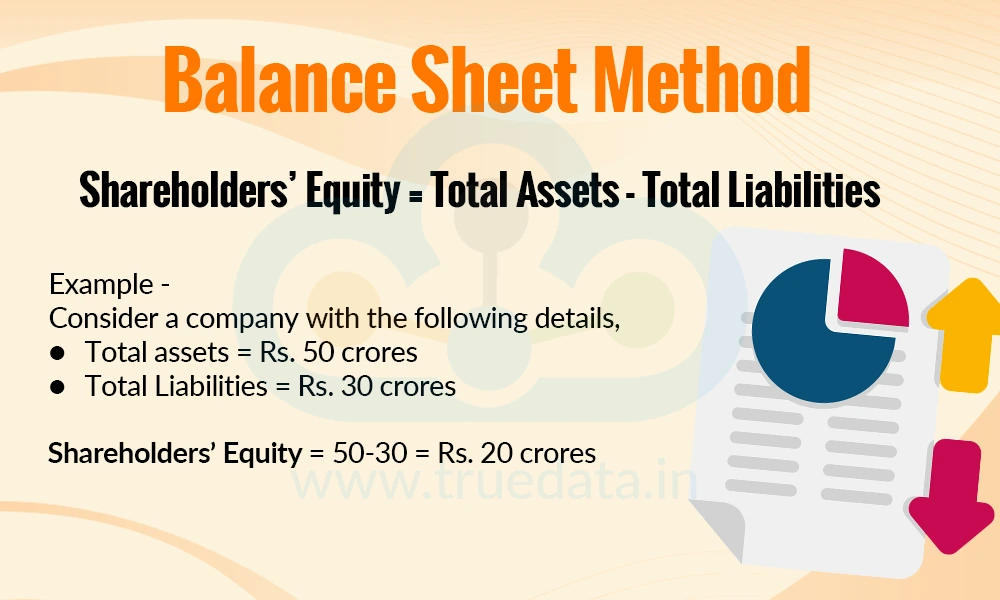

This method takes the total value of everything the company owns (assets) and subtracts everything it owes (liabilities), the result or the balance being the value that belongs to the shareholders.

The formula to calculate the Shareholders' Equity using the Balance Sheet method is,

Shareholders’ Equity = Total Assets - Total Liabilities

Example -

Consider a company with the following details,

Total assets = Rs. 50 crores

Total Liabilities = Rs. 30 crores

The Shareholders’ Equity in this case is calculated as under,

Shareholders’ Equity = Total Assets - Total Liabilities

Shareholders’ Equity = 50-30 = Rs. 20 crores

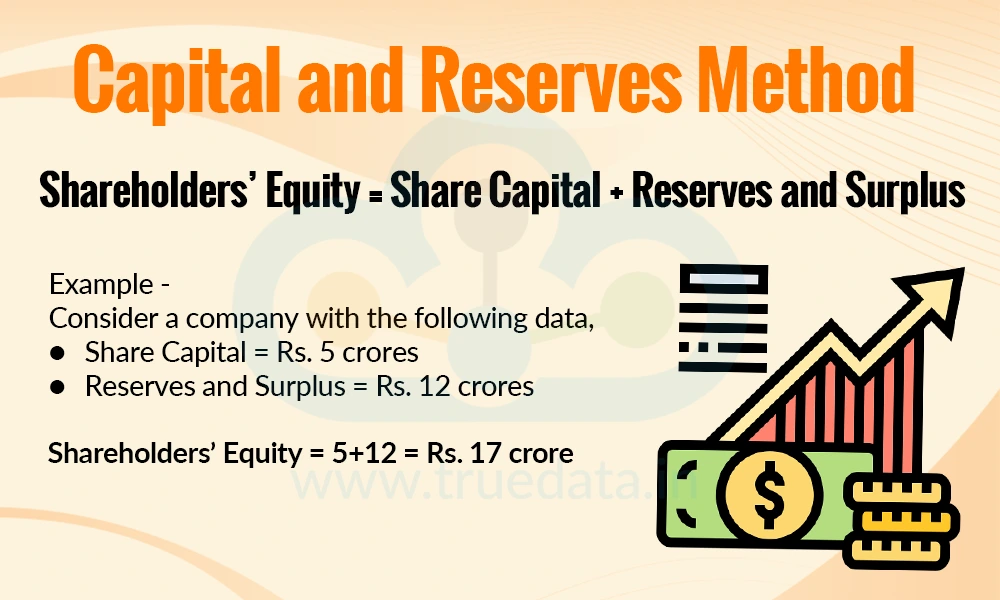

This method adds up the money shareholders have invested (share capital), the profits the company has kept aside (reserves and surplus), and any other comprehensive income. Then, if the company has bought back some of its own shares (treasury shares), that amount is subtracted.

The formula to calculate the Shareholders' Equity using the capital and reserves method is,

Shareholders’ Equity = Share Capital + Reserves and Surplus

Example -

Consider a company with the following data,

Share Capital = Rs. 5 crores

Reserves and Surplus = Rs. 12 crores

The Shareholders’ Equity in this case is calculated as under,

Shareholders’ Equity = Share Capital + Reserves and Surplus

Shareholders’ Equity = 5+12 = Rs. 17 crore

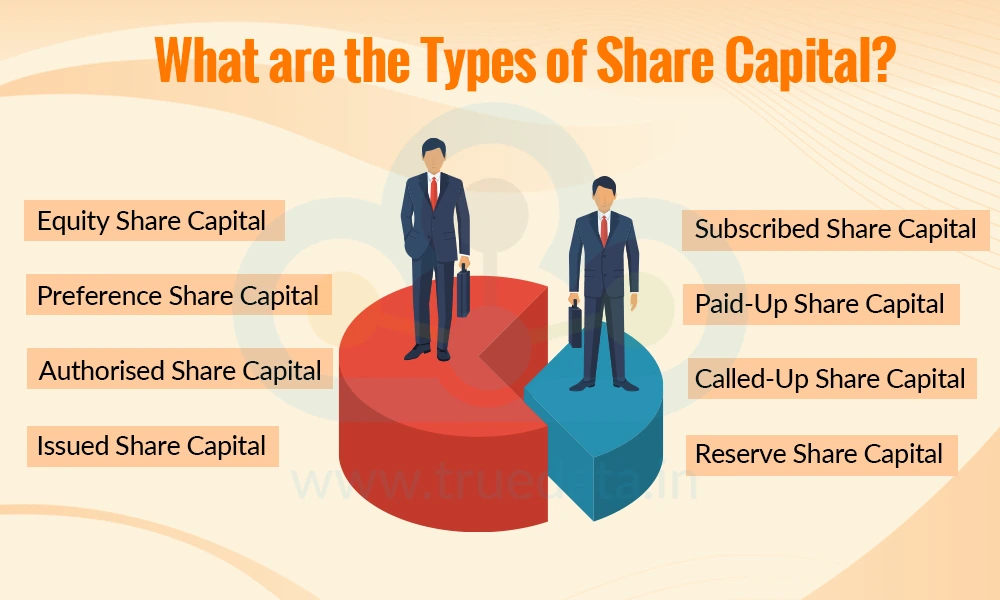

Share capital refers to the amount of money a company raises by issuing shares to investors. The Companies Act, 2013, governs the types and structure of share capital. Each type of share capital shows a different stage or purpose of fundraising for the company.

Equity share capital represents the money raised by issuing ordinary shares to investors. Holders of equity shares are the real owners of the company and have the right to vote on important matters such as electing directors, approving mergers, and changing the company’s structure. Their return comes mainly in the form of dividends, which are not fixed and depend on the company’s profits. In case the company winds up, equity shareholders are the last to be paid after all debts and dues of preference shareholders have been paid. Equity shares are the most common form of investment in a company because they offer ownership, voting rights, and the possibility of higher returns if the business grows, though they also carry higher risk.

Preference share capital represents the money raised by issuing shares that give their holders a priority claim over profits and assets. Preference shareholders are entitled to receive a fixed dividend before any dividends are given to equity shareholders. In the event of liquidation, they are also paid before equity shareholders, though after creditors. However, in most cases, preference shareholders do not have voting rights in company decisions unless their dividend payments are in arrears or a special condition arises. Companies often use preference shares to raise funds without giving away much control to investors. Preference shares can be attractive for investors as they offer steady income and reduced risk compared to equity shares. However, they usually offer less potential for capital growth.

Share capital is further classified into the following types.

Authorised share capital is the maximum amount of share capital that a company is allowed to raise by issuing shares, as stated in its Memorandum of Association. The company cannot issue more than this limit unless it changes its legal documents and gets shareholder approval. Thus, it is the company’s maximum potential for raising funds through shares. For example, if a company’s authorised capital is Rs. 50 crore, it can issue shares worth up to Rs. 50 crore, but not beyond that without approval.

Issued share capital is the portion of authorised capital that the company actually offers to investors for purchase. It can be equal to or less than the authorised capital. This portion shows how much of the potential share capital has been put into the market. For example, if a company has authorised capital of Rs. 50 crore, but issues shares worth Rs. 30 crore to investors, the issued share capital is Rs. 30 crore.

Subscribed share capital is the part of issued capital that investors have agreed to buy. Sometimes, investors may not buy all the shares the company offers. This portion indicates the actual investor interest in the shares offered. For example, if the company issues shares worth Rs. 30 crore but investors subscribe to only Rs. 25 crore, then the subscribed share capital is Rs. 25 crore.

Paid-up share capital is the amount actually received from shareholders on the called-up capital. It is the real money that the company has in hand from share sales or the actual capital received by the company from shareholders. For example, if the called-up amount is Rs. 6,00,000 but one shareholder still owes Rs. 50,000, then the paid-up share capital is Rs. 5,50,000. This is, thus, the actual capital received by the company from shareholders.

Called-up share capital is the amount the company has asked shareholders to pay on their subscribed shares. Companies sometimes collect share capital money in stages (for example, at the time of application, allotment, and later calls). For example, if a shareholder subscribes to Rs. 10,00,000 worth of shares but the company has so far asked for only Rs. 6,00,000, the called-up share capital is Rs. 6,00,000.

Reserve share capital is the portion of subscribed capital that a company decides not to call up unless it winds up or liquidates. This acts as a safety net for creditors during liquidation. For example, if a company has Rs. 20 crore in subscribed capital but decides that Rs. 2 crore will be reserved and only called upon winding up, that Rs. 2 crore is reserve share capital.

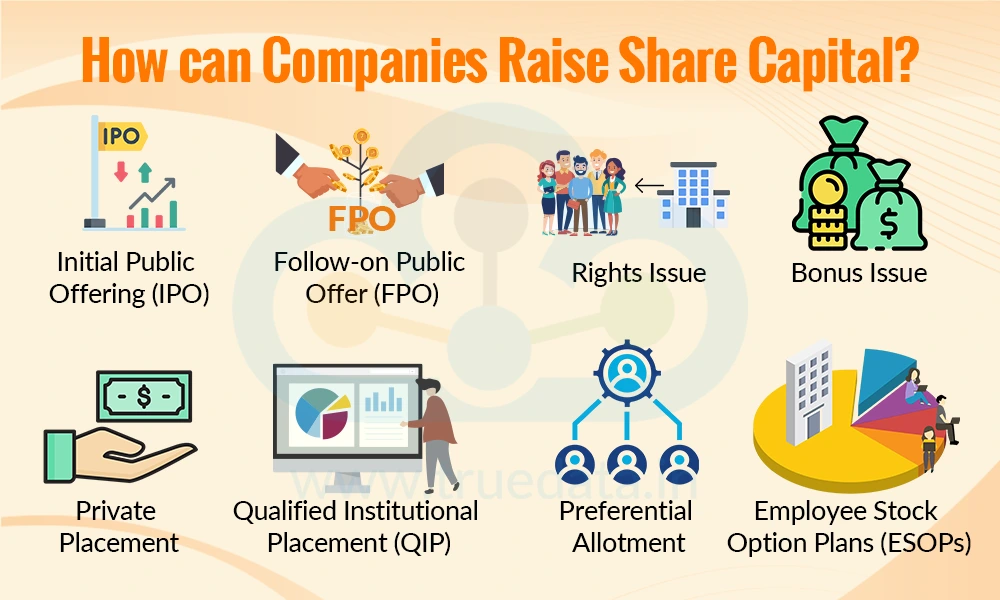

Share capital is the money a company collects from investors by issuing shares. Companies can raise share capital from various resources, depending on whether they are private or public, listed or unlisted. These resources are explained below.

An Initial Public Offering (IPO) is when a company sells its shares to the public for the first time through the stock exchange. This process turns a private company into a publicly listed one. An IPO is an opportunity for investors to become early shareholders in a company’s growth journey.

A Follow-on Public Offer happens when a company that is already listed on the stock exchange issues additional shares to raise more funds. This is often done to finance expansion, reduce debt, or strengthen working capital.

In a rights issue, the company offers new shares to its existing shareholders in proportion to their current holdings, often at a discounted price. This allows loyal investors to increase their stake in the company while providing the company with fresh funds.

A bonus issue involves giving free additional shares to existing shareholders, usually out of the company’s reserves, instead of paying cash dividends. While this does not directly bring in new funds, it increases the number of shares in the market and can make the stock more affordable to investors.

In a private placement, the company sells shares directly to a select group of investors, such as banks, financial institutions, or wealthy individuals, without offering them to the general public. This is a faster way to raise funds compared to a public issue.

A Qualified Institutional Placement allows a listed company to issue shares only to qualified institutional buyers like mutual funds, insurance companies, or pension funds. This is a popular method in India as it avoids lengthy regulatory procedures.

Preferential allotment means issuing shares to a specific group of investors, including promoters, at a pre-decided price. This method is commonly used for quick fundraising or to bring in strategic investors.

Under ESOPs, companies give their employees the right to buy shares at a fixed price after a certain period. When employees exercise these options, it increases the company’s share capital while also motivating staff loyalty.

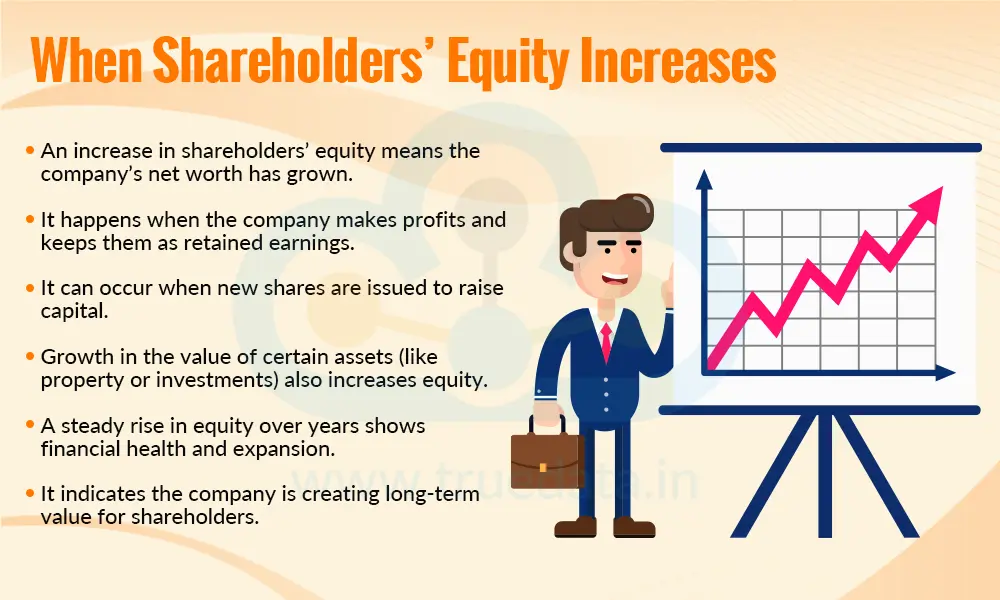

The increase or decrease in the shareholder equity represents the changes in the share capital or reserves, and surplus during the period of consideration. The interpretation of these changes is explained below.

An increase in shareholders’ equity usually means that the company’s net worth has grown. This can happen when the company makes profits and keeps them as retained earnings, issues new shares to raise capital, or sees an increase in the value of certain assets (like property or investments). A steady rise in equity over several years often indicates that the company is financially healthy, expanding, and creating long-term value for shareholders. It can also suggest that management is successfully reinvesting profits to grow the business.

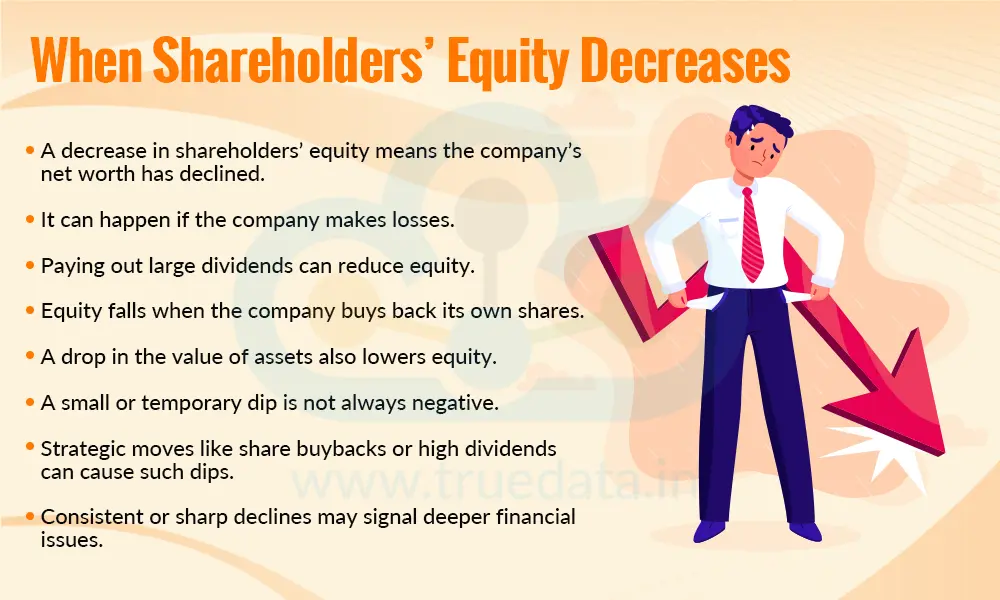

A decrease in shareholders’ equity means the company’s net worth has gone down. This can happen if the company makes losses, pays out large dividends, buys back its own shares, or suffers a drop in the value of its assets. A small or temporary dip is not always bad, especially if it is due to strategic moves like share buybacks or paying high dividends. However, consistent or sharp declines may signal deeper financial problems, such as falling profits or increasing debt, which could affect future returns.

As mentioned above, the shareholders’ equity accounts for the owners’ funds and can also be used to spot any potential red flags in the financial statements. These red flags include,

Consistently Declining Equity - If shareholders’ equity keeps falling year after year, it can mean the company is making losses, paying out more than it earns, or losing asset value. A steady decline may be a sign that the company’s financial health is weakening.

Negative Shareholders’ Equity - Negative equity means the company owes more than it owns, i.e., its liabilities are greater than its assets. This is a major warning sign and could indicate serious financial trouble. Some heavily debt-burdened companies have shown negative equity before going bankrupt.

Sudden Large Drops in Equity - A sharp fall in equity in a single year could mean big losses, heavy write-downs of assets, or significant payouts like special dividends. Investors should investigate the reason to see if it’s a temporary event or a sign of ongoing problems.

Equity Growth from Share Issues, Not Profits - If equity is increasing mainly because the company is issuing more shares instead of earning profits, it might mean the business is struggling to generate enough cash internally. This can dilute the ownership percentage of existing shareholders.

Frequent Share Buybacks Despite Weak Profits - While buybacks can be good for shareholders, if a company keeps buying back shares even when profits are low or debt is high, it could be using financial resources unwisely. This may harm its long-term stability.

Large or Unexplained Changes in Reserves - Sudden increases or decreases in reserves without a clear explanation can be a red flag. It may mean the company is making aggressive accounting adjustments or hiding underlying issues.

Frequent Changes in Share Capital Structure - Constant increases or decreases in share capital without a clear growth plan may suggest instability in the company’s funding strategy. Investors should check if these changes are for genuine expansion or to cover up cash flow problems.

Shareholders’ equity is a key measure of a company’s true worth, i.e., the value left for owners after paying all debts. It is made up of a few components that represent various forms of shareholders’ funds. Understanding the composition and type of shareholders' equity is crucial for judging a company’s financial strength, thereby shaping a robust portfolio.

This blog explains the final component of the balance sheet in detail. Let us know your thoughts on this topic or if you need further information on the same, and we will address it soon.

Till then, Happy Reading!

Read More: LODR Compliance - What is it and Why is it important?

Thestock market never stands still, and prices swing constantly with every new h...

Analysing the financial statements is the first step in the fundamental analysis...

Abalance sheet is built on two pillars, assets and liabilities. We have explored...